Vitreous loss is connected with a poor visual result following cataract surgery. Vitreous loss is less common among experienced surgeons and those who undertake a significant volume of cataract surgeries. Risk classification techniques exist to assist less experienced surgeons in avoiding high-risk patients. The treatment of vitreous loss entails counseling patients about the possible risks and problems prior to the cataract surgery.

When a vitreous loss occurs, it is critical for the surgeon to avoid behaviors that enhance the likelihood of an eye tragedy. These include phacoemulsification in the presence of vitreous and non-vitrectomy methods to retrieve lens pieces from the posterior region.

There are advantages to conducting an anterior vitrectomy via the pars plana pathway rather than the anterior chamber, and sutureless 23-gauge tools aid this method. Lens nuclear fragment dislocation into the vitreous is associated with an increased risk of retinal detachment, subsequent glaucoma, and cystoid macular edema. It is suggested that these eyes be managed promptly by a retinal surgeon.

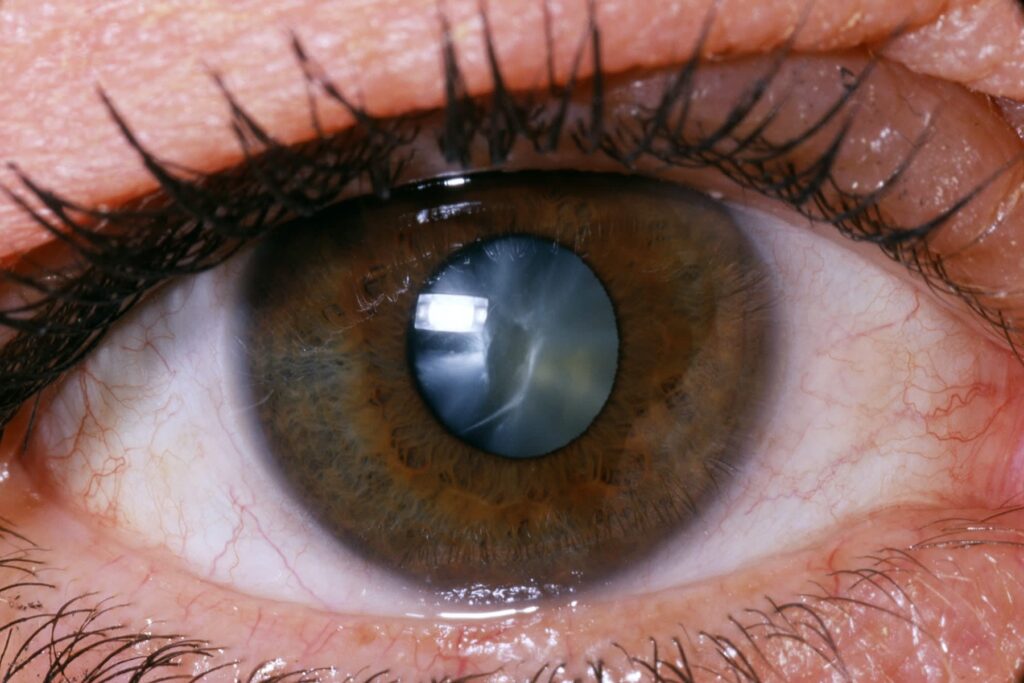

The posterior lens capsule is an anatomical barrier that protects the vitreous body from lens fragmentation, aspiration, and intraocular lens implantation stresses. In the 1997–1998 UK national cataract surgery study, capsule rupture and vitreous loss occurred in 4.4 percent of patients. Other papers indicate rates ranging between 8.22 and 0.45 percent of patients. Vitreous degeneration is associated with an increased risk of vision-threatening consequences such as cystoid macular edema, retinal detachment, and endophthalmitis. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 Disruption of the posterior capsule may be followed by displacement of lens pieces into the posterior segment, resulting in an even poorer prognosis for those eyes.

Prevention

The nitty-gritty of safe cataract surgery is beyond the scope of this essay and is covered in current literature.

Vitreous loss is dependent on the surgeon’s experience,6 surgical volumes (number of cataract procedures performed per surgeon per year),12, 13, and the complexity of cases or case-mix. Scoring systems enable a quantifiable estimate of risk in individual instances prior to the cataract surgery. Such risk categorization enables difficulties to be predicted and avoided via proper patient preparation, anesthetic type, and surgeon selection. Muhtaseb has shown that even experienced consultants had an 8% vitreous loss rate and a 4% fallen lens nucleus rate in high-risk eyes. Cataract surgery in such eyes appears to be best performed by surgeons skilled in vitrectomy and the removal of displaced lens components from the posterior region.

While the critical role of the capsulorhexis in the outcome of cataract surgery has been correctly stressed17, the quality of the capsulorhexis may be established much earlier in the operation by factors such as patient preparation, anesthetic choice, and wound architecture. Difficulties may arise even with flawless capsulorhexis in high-risk eyes, such as after vitrectomy18, when an unstable anterior chamber depth results in anterior chamber depth variations, pupil constriction, and patient discomfort. 19 It is necessary to understand how to manage these eyes.

The patient’s management

Cataract surgery is not a routine procedure, but people have come to expect it to be. If informed consent included a discussion of anticipated vitreous loss, lens matter displacement, and failure to implant an intraocular lens, managing a substantial intraoperative complication will be easier for the patient. This will alleviate patient anxiety and contribute to the patient and surgeon developing trust during and after the cataract surgery procedure. Patients want to be advised of uncommon consequences; 93.5 percent want to be notified if the risk is one in 50, and 62.4 percent want to be informed if the risk is one in 1000. However, recall accuracy of consent information is low, particularly for significant problems, creating a barrier in preparing patients for potentially problematic operations.

Management: the watchful eye

Recognition of vitreous loss will be indicated by a slight but abrupt change in the internal circumstances of the eye. One or more of the following signs may be observed: sudden chamber deepening, altered lens nucleus mobility, excessive sideways displacement of the nucleus, the sudden appearance of a red reflex, and abnormal movement of structures (for example, the pupil margin) remote from instruments in the anterior chamber caused by traction transmitted through vitreous strands. You can read about Things you shouldn’t dare to do after cataract surgery by visiting https://davidsnieckus.com/things-you-shouldnt-dare-to-do-after-a-cataract-surgery/

If phacoemulsification is still being performed, it should be halted and the probe should be gently removed from the eye in a manner that minimizes tension on the vitreous. At this point, a viscoelastic material may be injected into the anterior chamber to help prevent vitreous prolapse when the phacoemulsification probe is removed and to help stabilize any residual lens pieces. It is critical that the surgeon then take a moment of meditation. While the condition is being assessed, time can be productively used by setting up the vitrectomy apparatus and, if necessary, applying a sub-anesthetic. Tenon’s Delayed response at this point may allow for the posterior sinking of the lens nucleus or large sections of lens material. This is a manageable issue that often has a favorable outcome. Precipitate and forceful attempts at lens fragment retrieval through an anterior technique are detrimental. Click here to read about the phacoemulsification probe.

The objectives of vitreous loss management are to remove any vitreous from the anterior chamber and surgical site to complete cataract surgery, and to implant an intraocular lens safely. It is appropriate for the primary surgeon to accomplish some, all, or none of these tasks, depending on the surgeon’s skill and the complexity of the given case. Vitreous should be eliminated using a vitreous cutter and a separate infusion given by an anterior chamber maintainer. The use of a coaxial infusion sleeve around a vitreous cutter is not suggested because it creates a flow conflict between infusion and aspiration, and control of intraocular pressure is lost each time the cutter is withdrawn from the eye.

The inability of so-called ‘dry’ vitrectomy procedures to maintain a consistent intraocular pressure is a limitation. To extract vitreous from the anterior chamber, the cutter should be inserted through the pars plana, using either an anterior chamber or pars plana infusion. 25 This minimizes anterior chamber manipulation, minimizes vitreous imprisonment in the corneal incision, and enables vitreous removal deep behind the posterior capsule, which is more difficult and hazardous when the cutter is inserted through the anterior chamber. Although triamcinolone particles may be utilized to see vitreous strands in the anterior chamber, their usage is not required.

Sutureless vitrectomy using a 25-gauge needle was employed. The larger 23-gauge sutureless instruments provide more control and may be more effective in dealing with retained lens material as well as vitreous. A vitrector is an excellent tool for removing soft lens debris. After the anterior chamber has been entirely cleaned of vitreous, nuclear material can be emulsified and aspirated by reintroducing the phacoemulsification probe, or intact nuclear fragments can be removed through an expanded incision. Before removing nuclear fragments from the anterior chamber, viscoelastic or a lens glide29 may be used to stabilize them.

If nuclear pieces are displaced posteriorly behind the plane of the posterior capsule, forceful attempts to extract them without pars plana vitrectomy can result in massive retinal tears and detachment.